According to a report issued last week, the U.S. Forest Service and the Department of the Interior are projected to spend over $470 million more than Congress has budgeted to fight wildfires this year.

The Congressionally-mandated report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which incorporates the Forest Service, projects that the two largest federal wildfire firefighting agencies may need to spend $1.8 billion fighting fires, while the agencies have only $1.4 billion in allocated funds available for firefighting.

“The forecast released today demonstrates the difficult budget position the Forest Service and Interior face in our efforts to fight catastrophic wildfire,” said Robert Bonnie, Under Secretary of Agriculture for Natural Resources and Environment, last week. “While our agencies will spend the necessary resources to protect people, homes, and our forests, the high levels of wildfire this report predicts would force us to borrow funds from forest restoration, recreation, and other areas.”

Drought conditions in the West, especially in California, are at the center of the report’s projections. If the fire season is as costly as the report predicts, the Forest Service and Interior Department will be forced to transfer money from other programs directly to battling blazes. In seven of the last 12 years, both departments have run out of funding to fight fires and have had to resort to this controversial practice.

While Congress has paid back most of the borrowed funds in the past, Forest Service Chief Tom Tidwell called the approach “nonsensical,” as the Forest Service is forced to borrow from programs that help to prevent future wildfire destruction, such as mechanical thinning and prescribed burning.

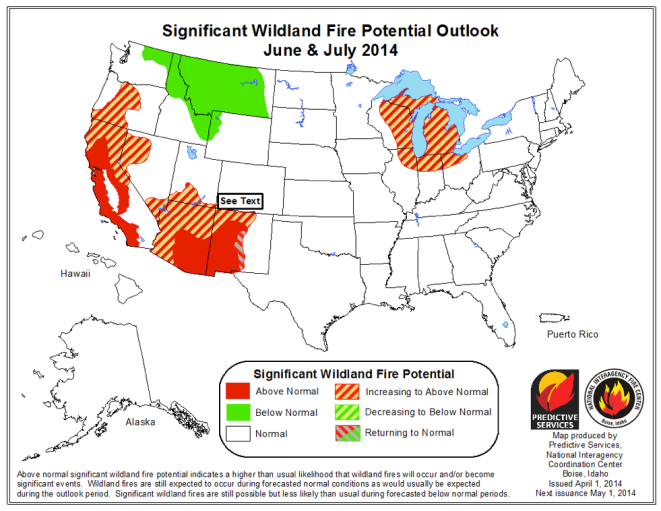

The National Interagency Fire Center predicts that California, Arizona, and New Mexico are primed for another bad wildfire season.

The National Interagency Fire Center predicts that California, Arizona, and New Mexico are primed for another bad wildfire season.

“We can suppress about 99 percent of all of fires within a reasonable, annual budget,” said Interior Secretary Sally Jewell. “But there’s one percent of fires, like for example the Yosemite Rim Fire last year, that truly are emergencies.”

The Rim Fire, which consumed over 250,000 acres in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains from August to October of last year, destroyed homes and threatened the Bay Area’s electricity and water supplies. When all was said and done, the fire ended up costing the federal government more than $100 million.

Obama to the rescue?

In March, the Obama administration proposed changing how the federal government funds wildfire suppression.

Based on bipartisan bills introduced in the House and Senate, the funding change would give the Forest Service and Interior Department access to the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Disaster Relief Fund. Created in 2011, the emergency fund is currently devoted to relief efforts associated with the aftermath of hurricanes, tornadoes, and major floods, but the change, which requires congressional action, would add large wildfires to the list. According to the White House, the largest one percent of wildfires consume over 30 percent of annual federal wildfire suppression costs.

“The President’s budget proposal, and similar bipartisan legislation before Congress, would solve this problem and allow the Forest Service to do more to restore our forests to make them more resistant to fire,” said Bonnie.

Despite support from western Republicans in the House and Senate, and a broad coalition of interest groups including both environmental activists and timber producers, the funding proposal has drawn scant interest from Republicans east of the Rocky Mountains, and opposition from House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan.

“Preventing and fighting wildfires are national priorities, and the president should budget accordingly,” said Ryan, a Republican from Wisconsin. “Yet the president is asking for $1.2 billion less than what he believes is necessary.”

Along with last year’s across-the-board sequestration cuts, Congress recently agreed to caps on discretionary spending, putting added cost pressures on federal firefighting agencies. “The fact that the President refused to use one-tenth of one percent of that money to fully fund wildfire prevention and suppression speaks to his real priorities,” said Ryan.

Proponents argue that the $12 billion Disaster Relief Fund, which falls outside discretionary budget limits, has gone largely unspent in recent years, giving the Obama administration a clear solution to address wildfire-funding shortfalls.

“Fire is every bit as much an emergency as a tornado or a hurricane,” said Rep. Mike Simpson, a Republican from Idaho who supports the Obama administration’s proposal.

Whether the funding change can make it past fiscally conservative Republicans in eastern states remains to be seen, but another bad wildfire season could put added pressure on lawmakers to make the change.

The rise of ‘megafires’

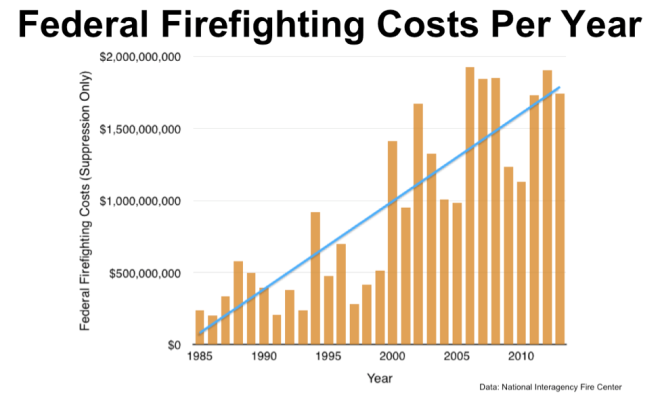

According to data from the National Interagency Fire Center, wildfires have been taking an increasingly larger toll in western states over the last 30 years, and the Obama administration thinks global warming is to blame.

“We know that future generations will continue to deal with the effects of a warming planet, so this budget proposes a smarter way to address the costs of wildfires,” said President Barack Obama in a speech in March.

According to a 2012 report by the nonprofit Climate Central, as temperatures have risen in western states, so too has the number of large wildfires, dubbed ‘megafires’ by some. Their data shows that as temperatures have increased since 1970, spring snowpack in western states has decreased. The report concludes that this process leads to longer, drier wildfire seasons, and that means bigger, more intense wildfires.

Another report, by the Department of Agriculture, predicts that as temperatures continue to rise, the acreage burned by wildfires will be around 20 million acres annually by 2050, more than double some of the worst, and most costly, fire seasons in recent history.

But according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, there is not yet an established scientific consensus on the link between global warming and wildfires. In fact, some climate models project California, which is in the midst of a historic drought, to get wetter, not drier, as a result of climate change.

Some critics believe that the Obama administration is cherry-picking scientific studies that fit their narrative in an attempt to push the wildfire funding change through Congress.

“It’s a great political strategy and entirely typical of bureaucracies to jump on a bandwagon of any perceived crisis to claim that they deserve some of the largess Congress gives out to mitigate that crisis,” said Randall O’Toole, Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. “But that doesn’t make it good public policy.”

A smarter way to address the costs of wildfire or another blank check for wildfire firefighting?

“One reason why fire has gotten so expensive is that Congress doesn’t know what to do about fire, so it just throws money at it,” said O’Toole.

In 2009, Congress passed and Obama signed the FLAME — Federal Land Assistance, Management, and Enhancement — Act, which established an emergency fund for fire suppression in the hopes of preventing borrowing. The FLAME Act allowed federal firefighting agencies to contribute unspent suppression money to the emergency fund during slow fire years and draw from it during bad fire years.

But Congress has repeatedly taken money from the fund, including $200 million in 2011 as a part of the deal to end the debt-ceiling standoff. Underfunding of the emergency fund, along with a series of bad fire seasons in recent years, have kept the FLAME Act from achieving its intended purpose. The Forest Service and Interior Department have run out of allocated funds to fight fires in each of the last two years.

Andy Stahl, Executive Director of Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics, sees wasteful spending as the biggest reason for the rise in federal firefighting costs. He calls the administration’s proposal “another blank check for firefighting that does nothing to contain costs.”

According to Tim Ingalesbee, Director of the Association for Fire Ecology, the Forest Service and Interior Department are the only federal agencies other than the Department of Defense that are authorized to spend borrowed money. Ingalesbee suggests that there are no incentives to control costs because the Forest Service and Interior Department know that Congress will pay back what they are forced to borrow from other funds.

Jerry Williams, former Forest Service National Director of Fire and Aviation, doesn’t see the wasteful spending that some claim.

“Too much fuel, having accumulated for too many years — in the presence of drought — is at the heart of the problem,” said Williams.

According to Williams, the federal government used to have a policy of putting out all fires on public land as soon as they were spotted. But this was bad for forest ecosystems, and also for humans as dead trees and other flammable organic materials accumulated without the natural presence of wildfire. Now, at the same time global warming is ushering in longer and drier fire seasons, Williams says we’re seeing the consequences of this policy.

“I understand the need to slow the hemorrhaging,” said Williams. “The key to reigning in suppression costs — and reducing the losses and damages that accompany these fires — hinges on our country’s will to deal with the fuel build-up issue.”

Correcting past public land management mistakes will require time, and money, in the short-term, but it will be worth it in the long-run, says Williams.

In the meantime, states like California are gearing up for what is likely to be another bad fire season. But with the Rim Fire in the back of California congressmen’s minds, they are unlikely to take the steps needed to return wildfires, or firefighting budgets, to a healthy state.

“When bad fires threaten high values, public and political leaders usually demand that the agencies ‘do more,’” said Williams. “In the middle of an emergency, there’s usually not much enthusiasm for cost control.”